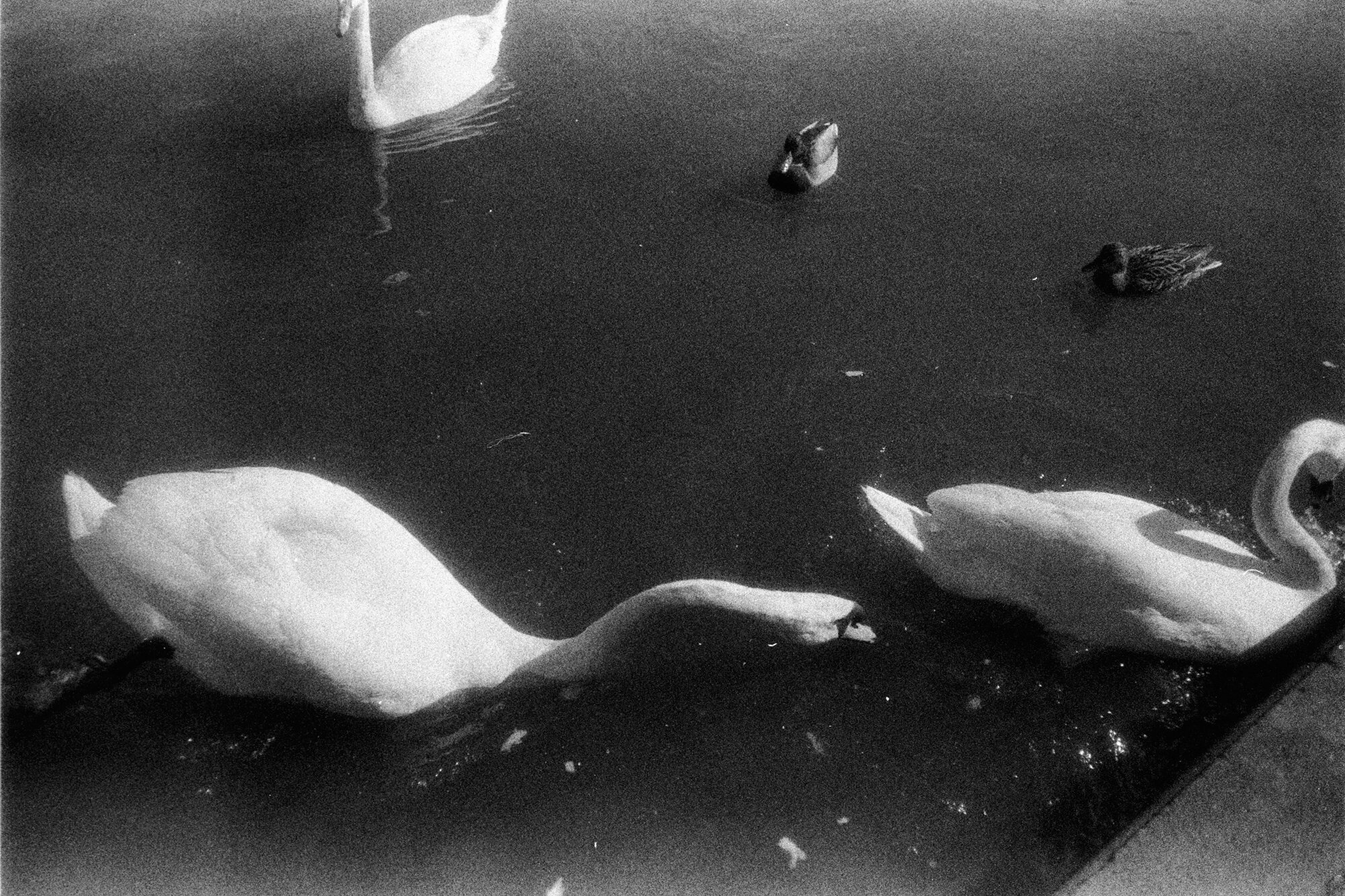

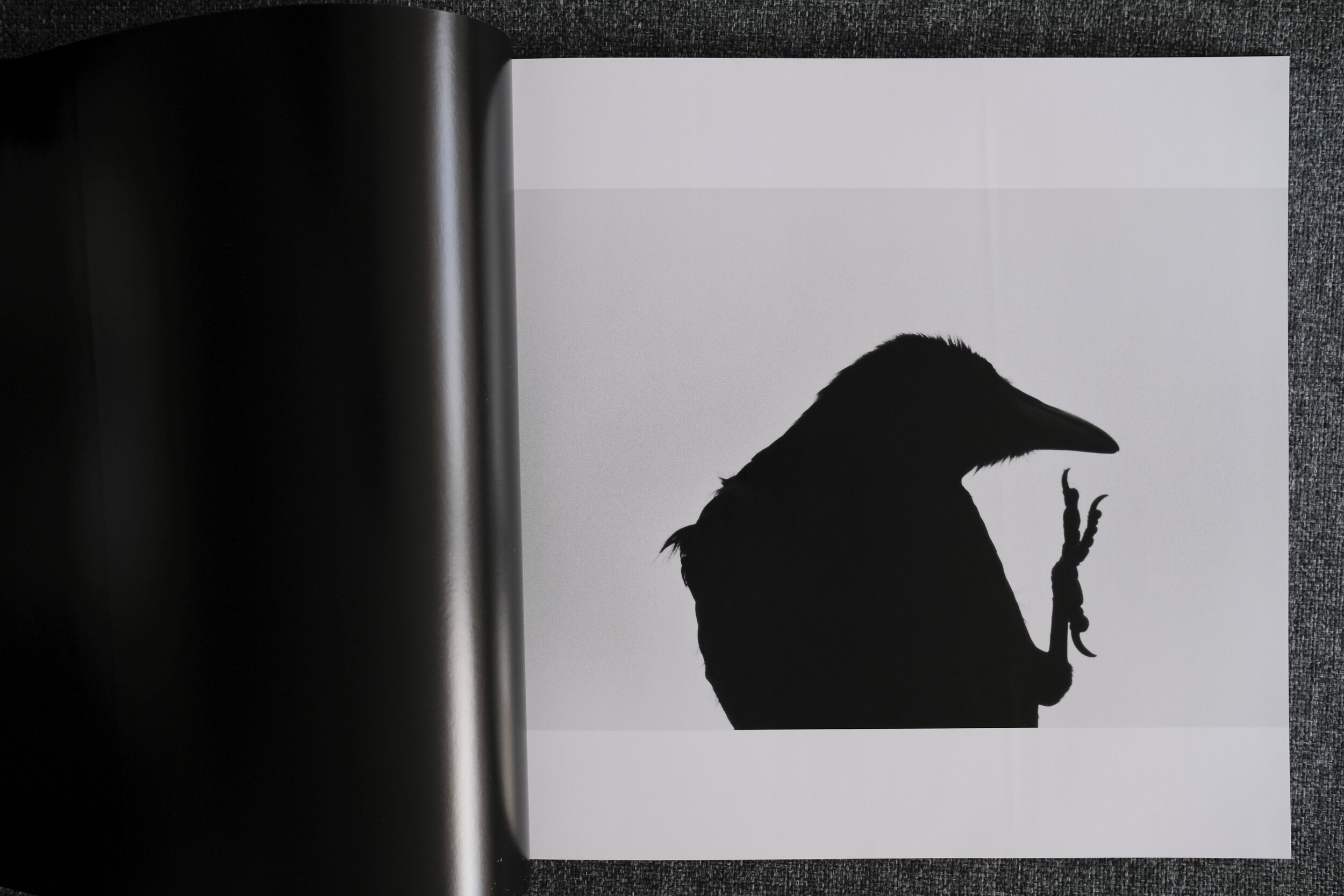

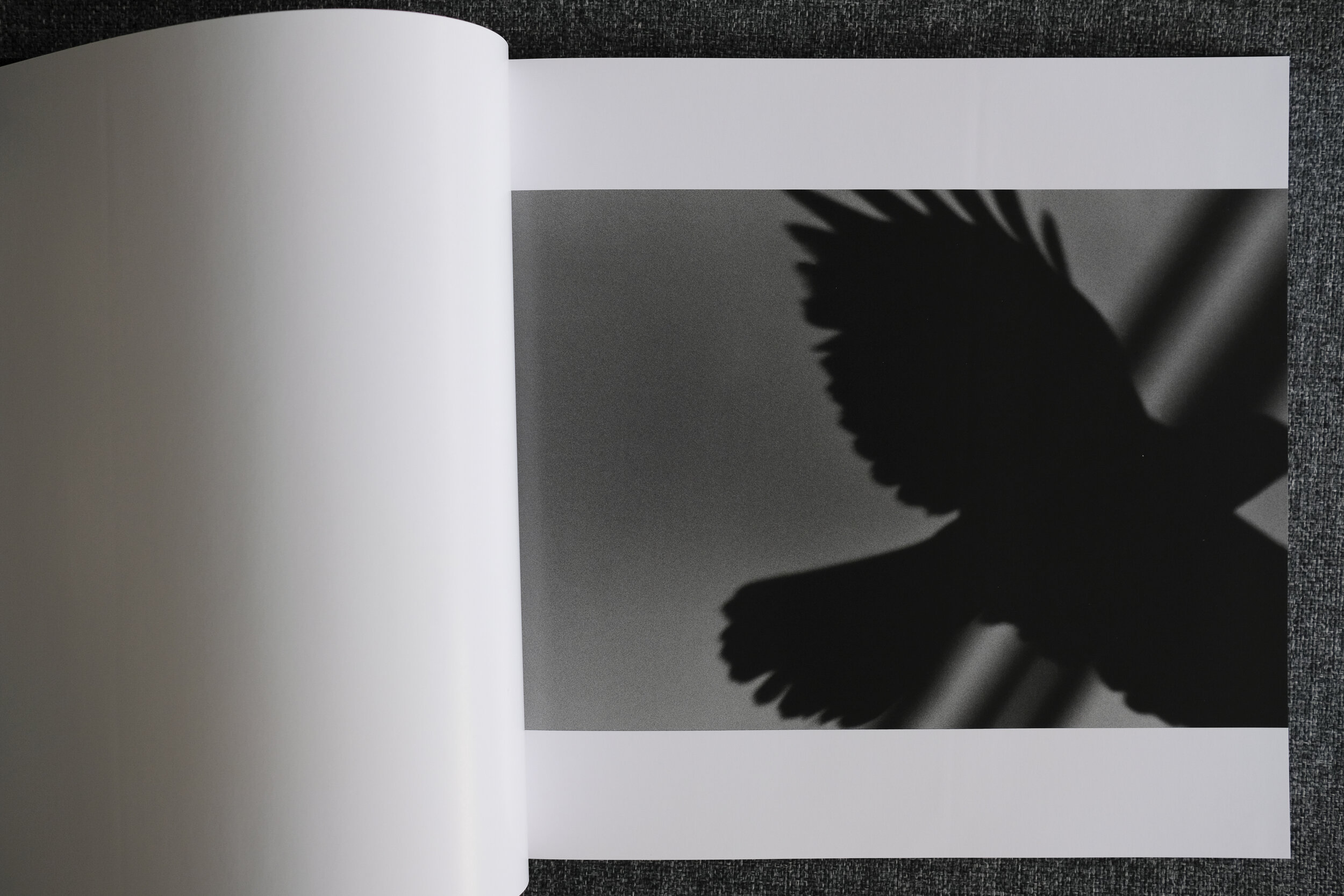

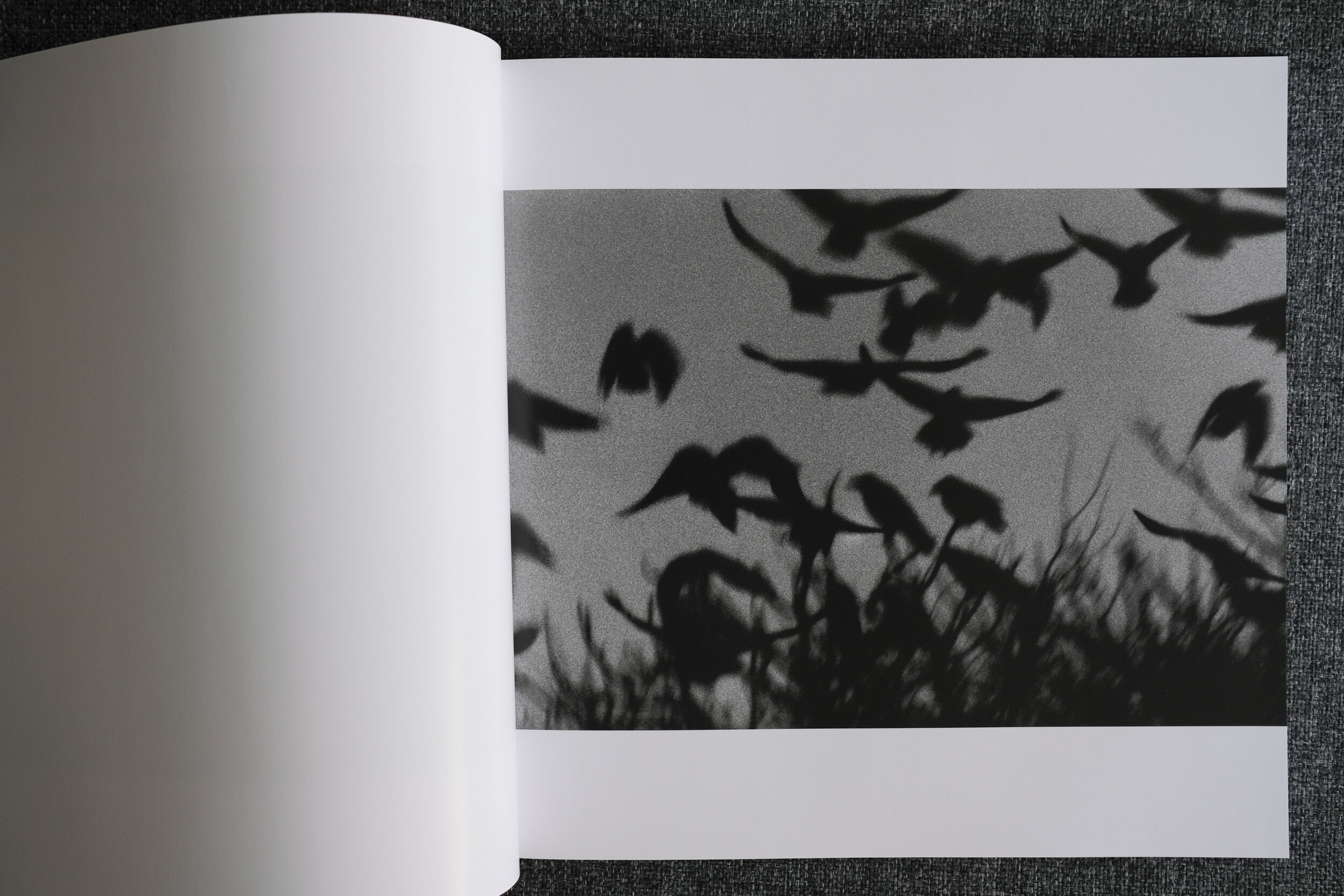

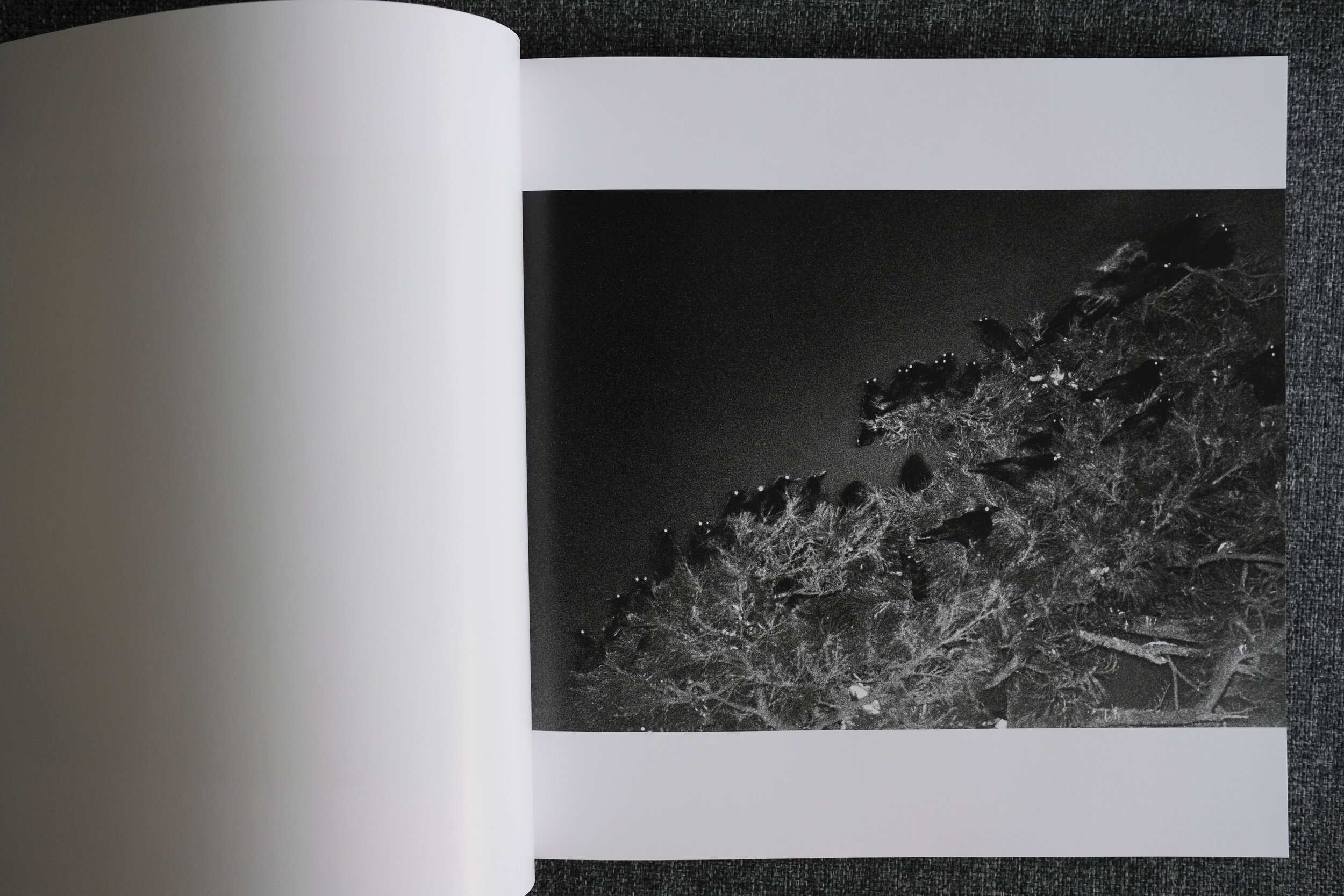

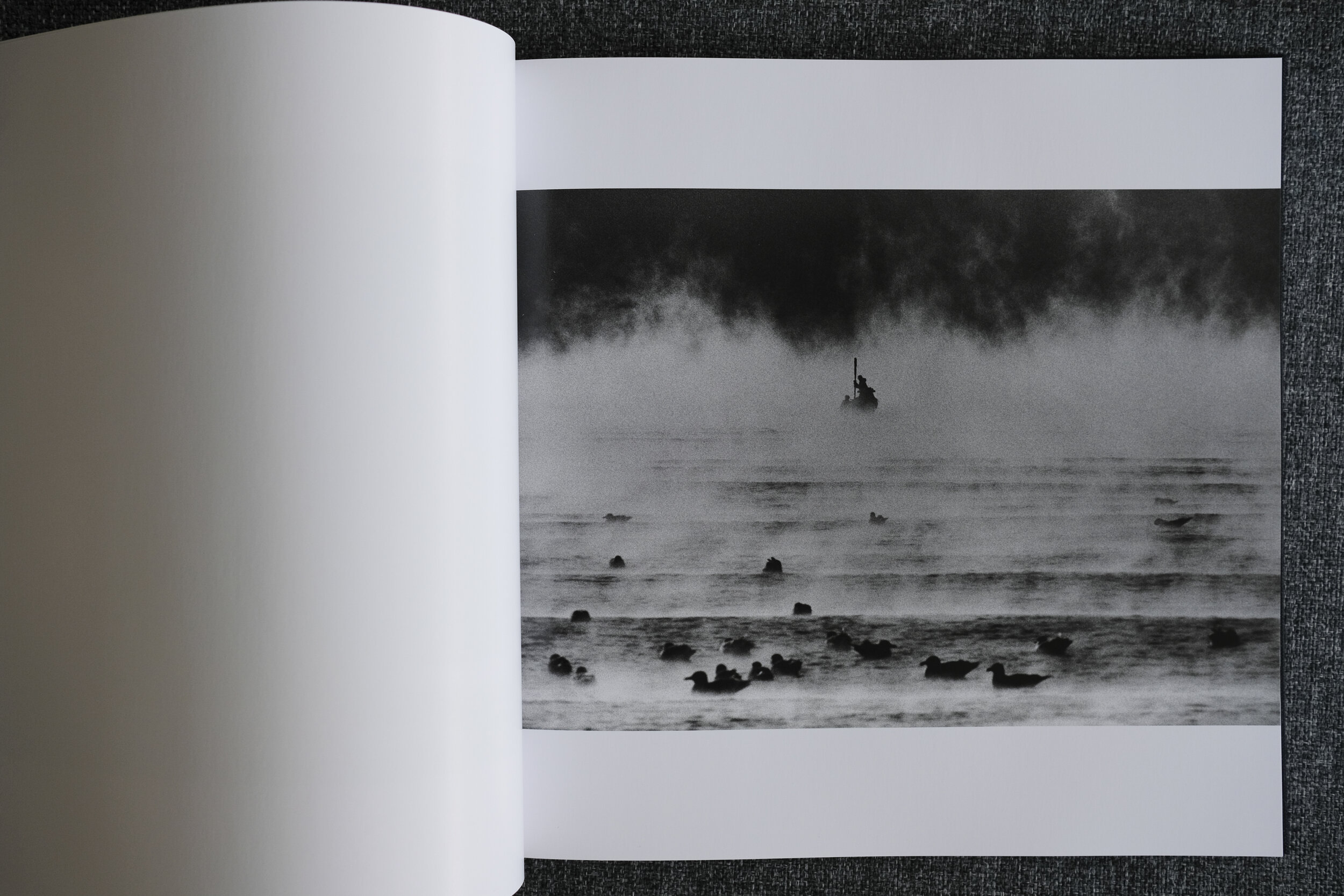

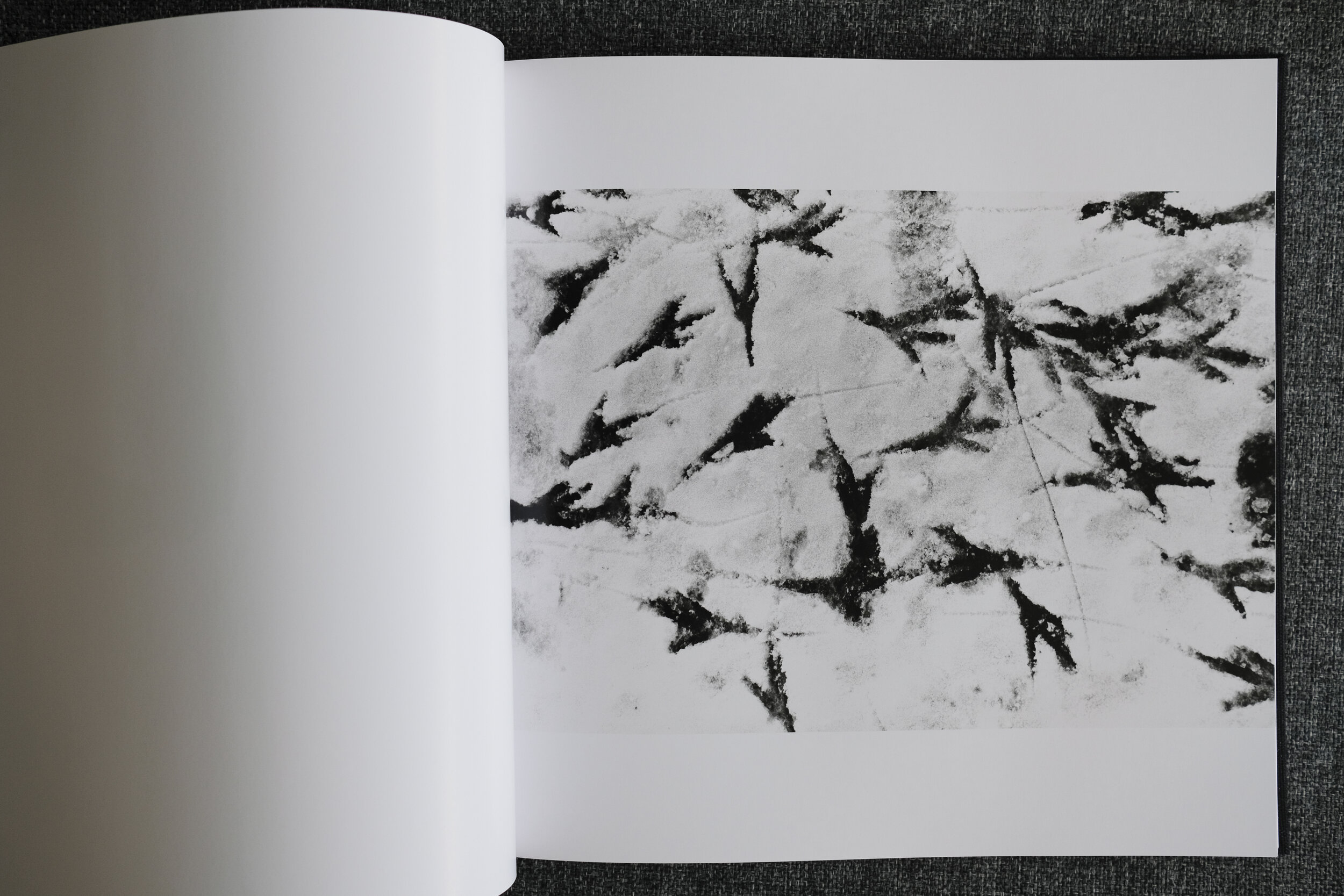

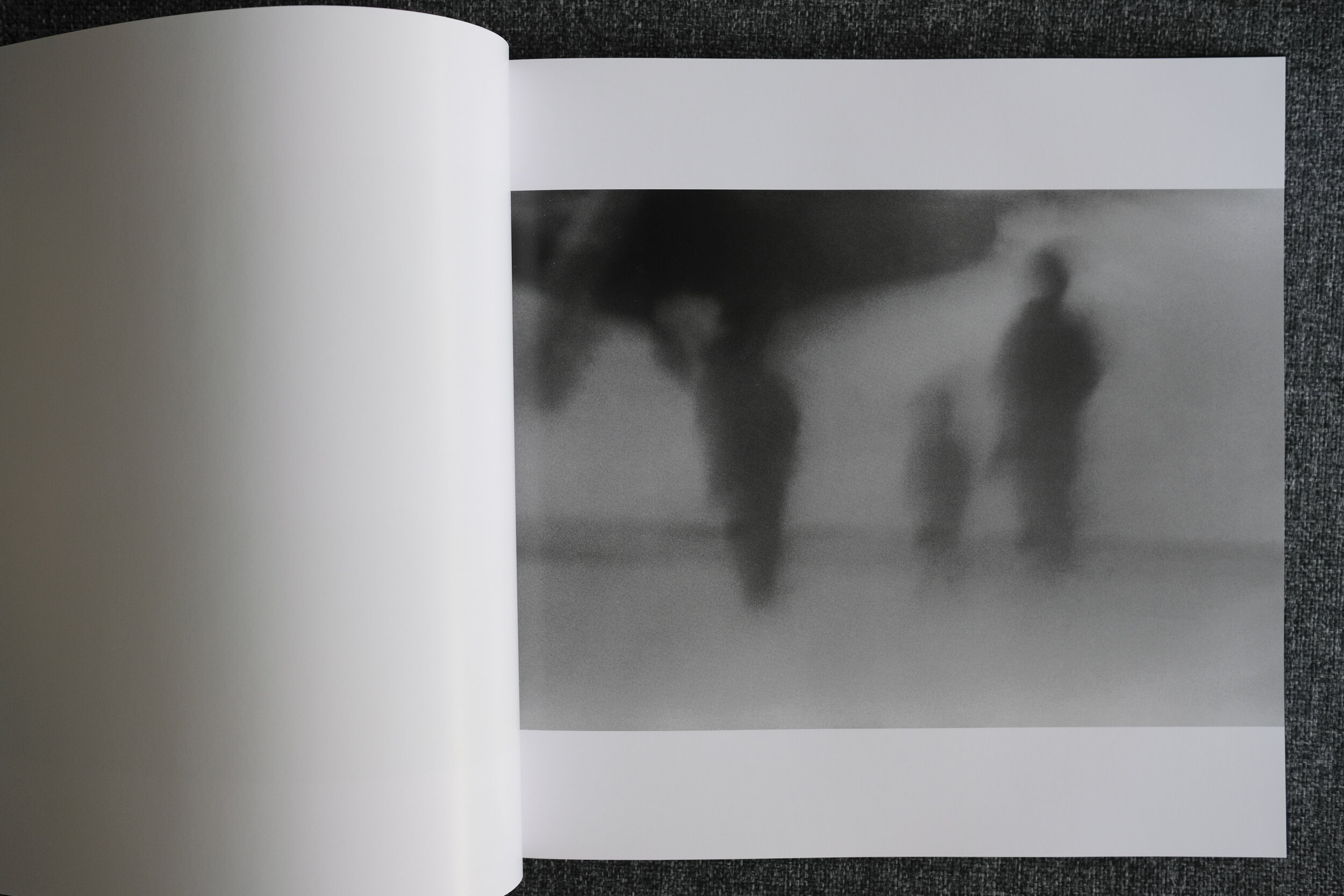

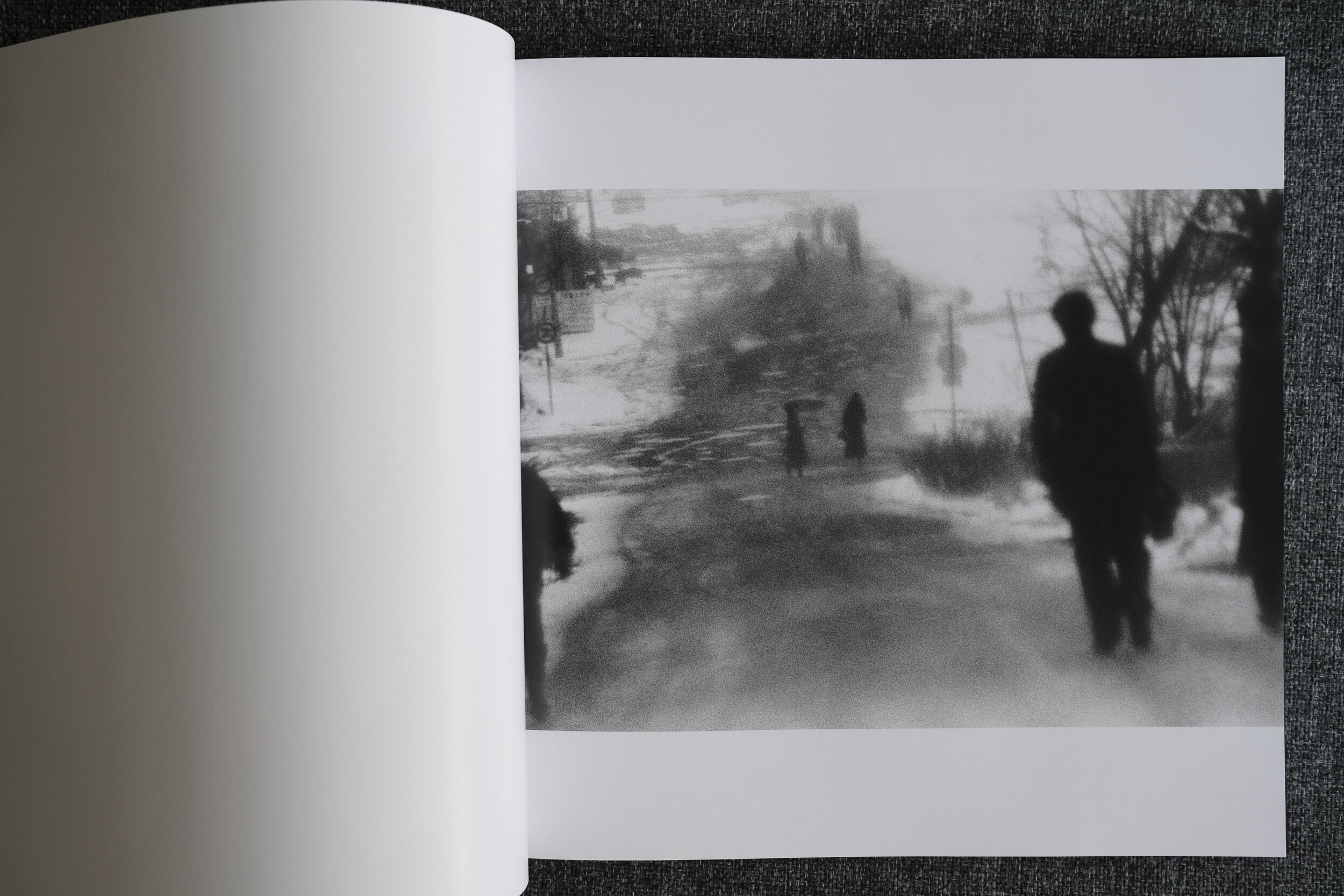

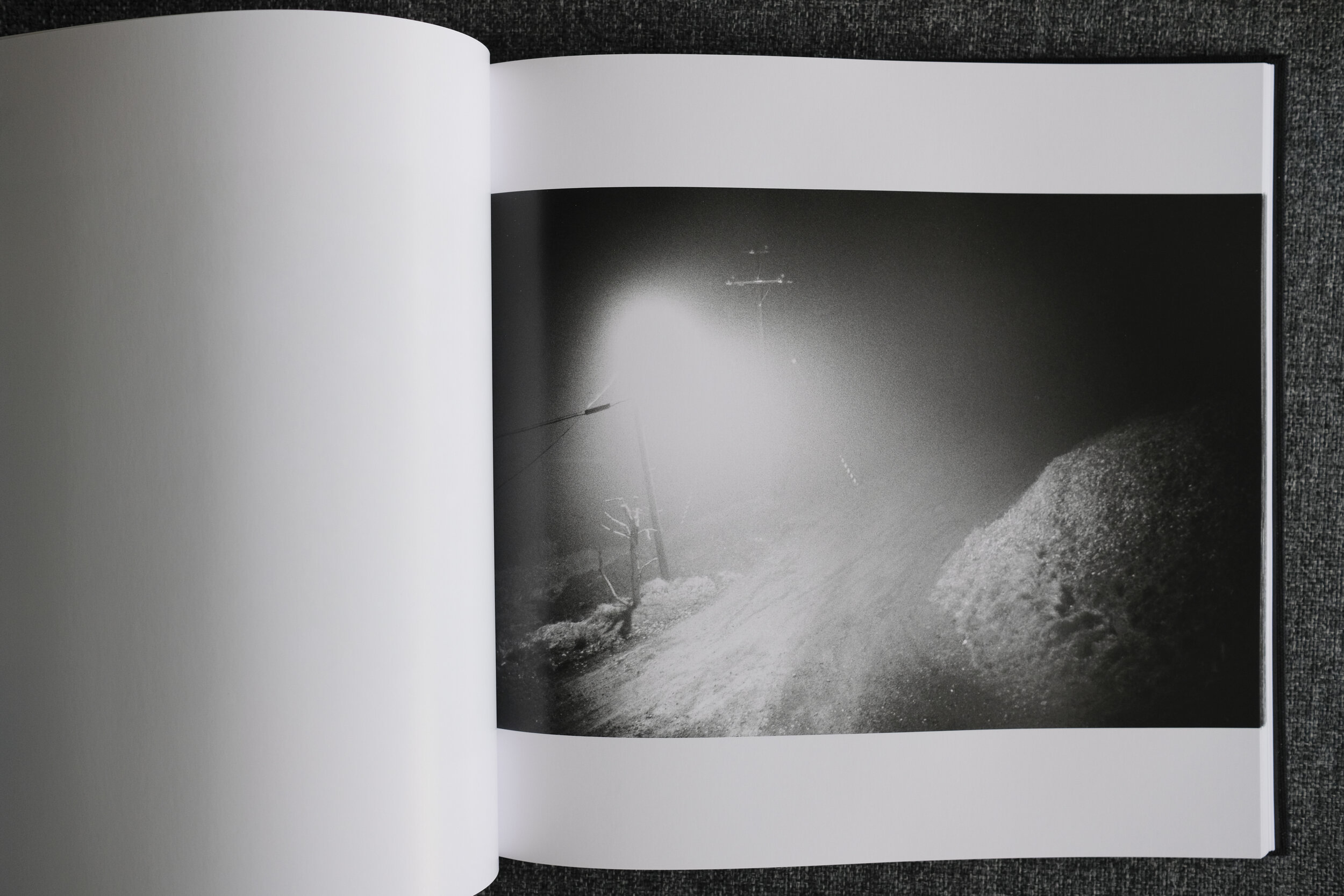

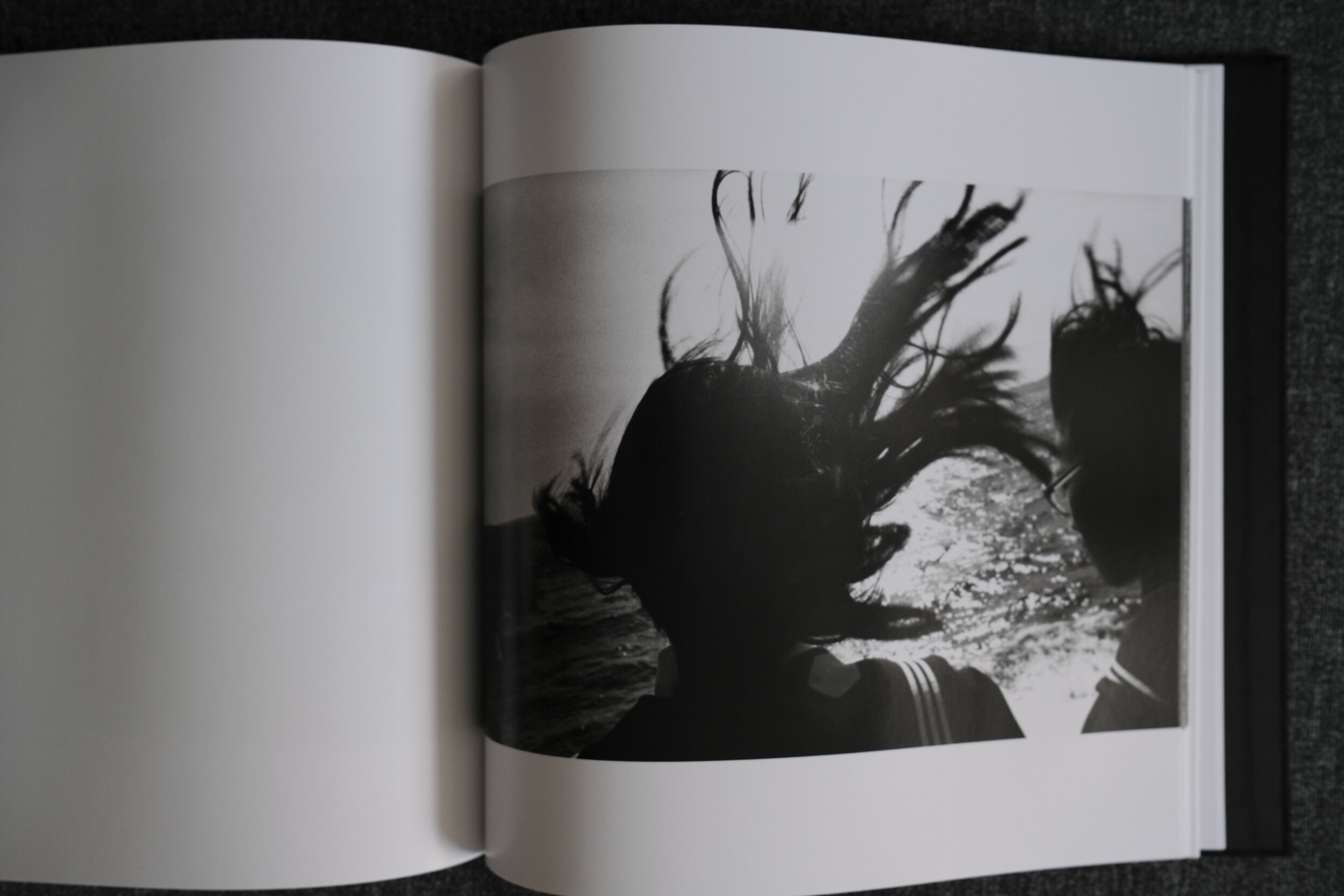

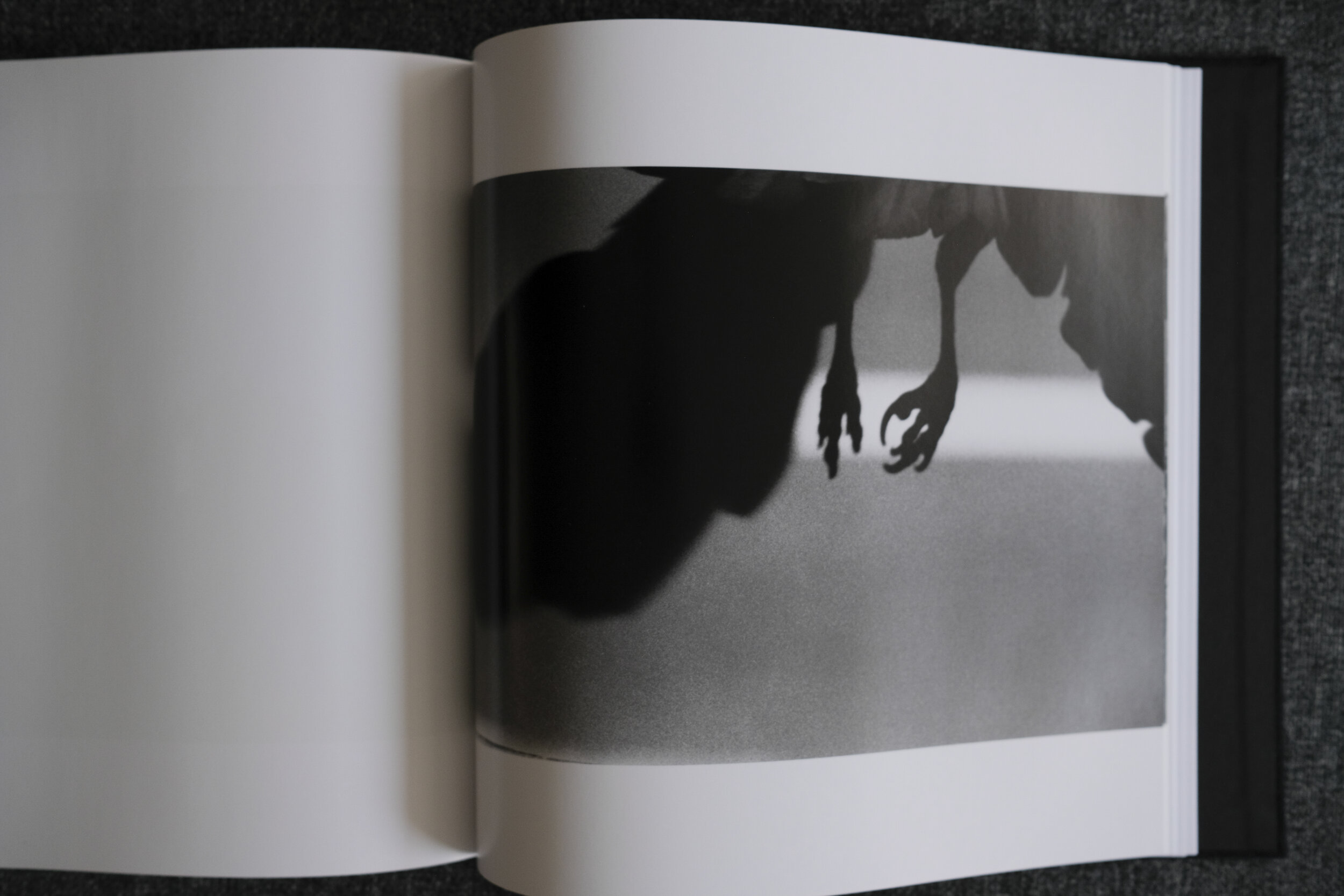

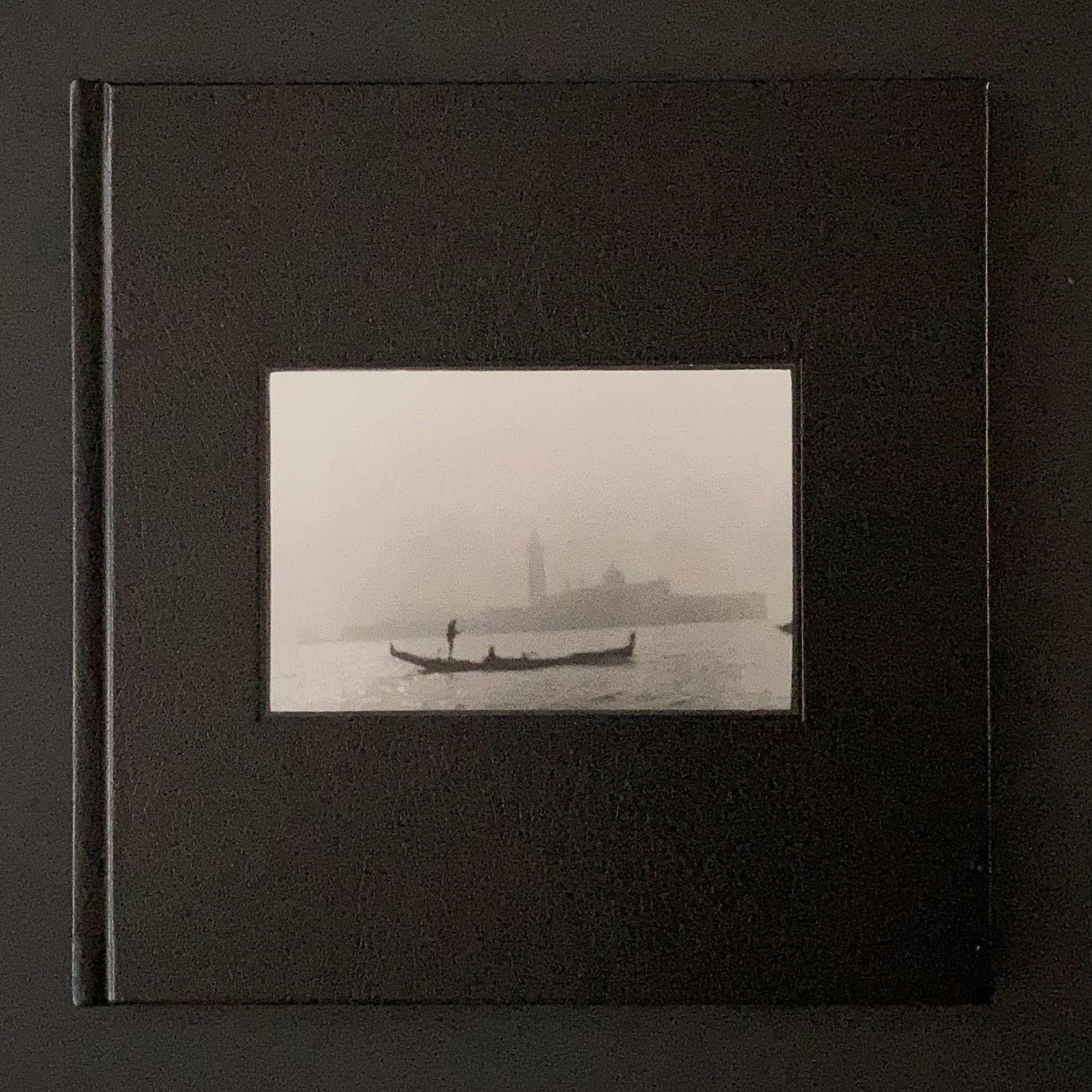

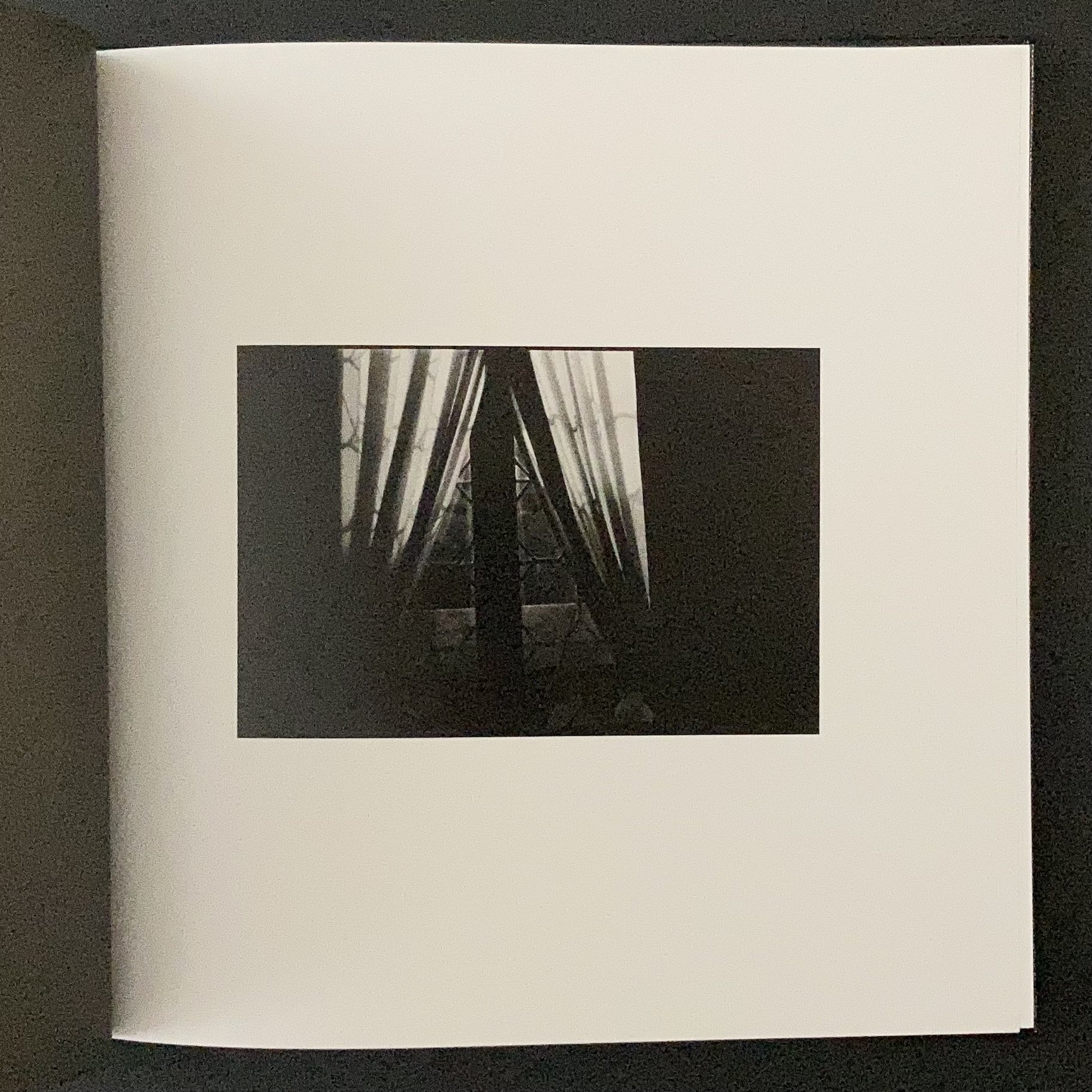

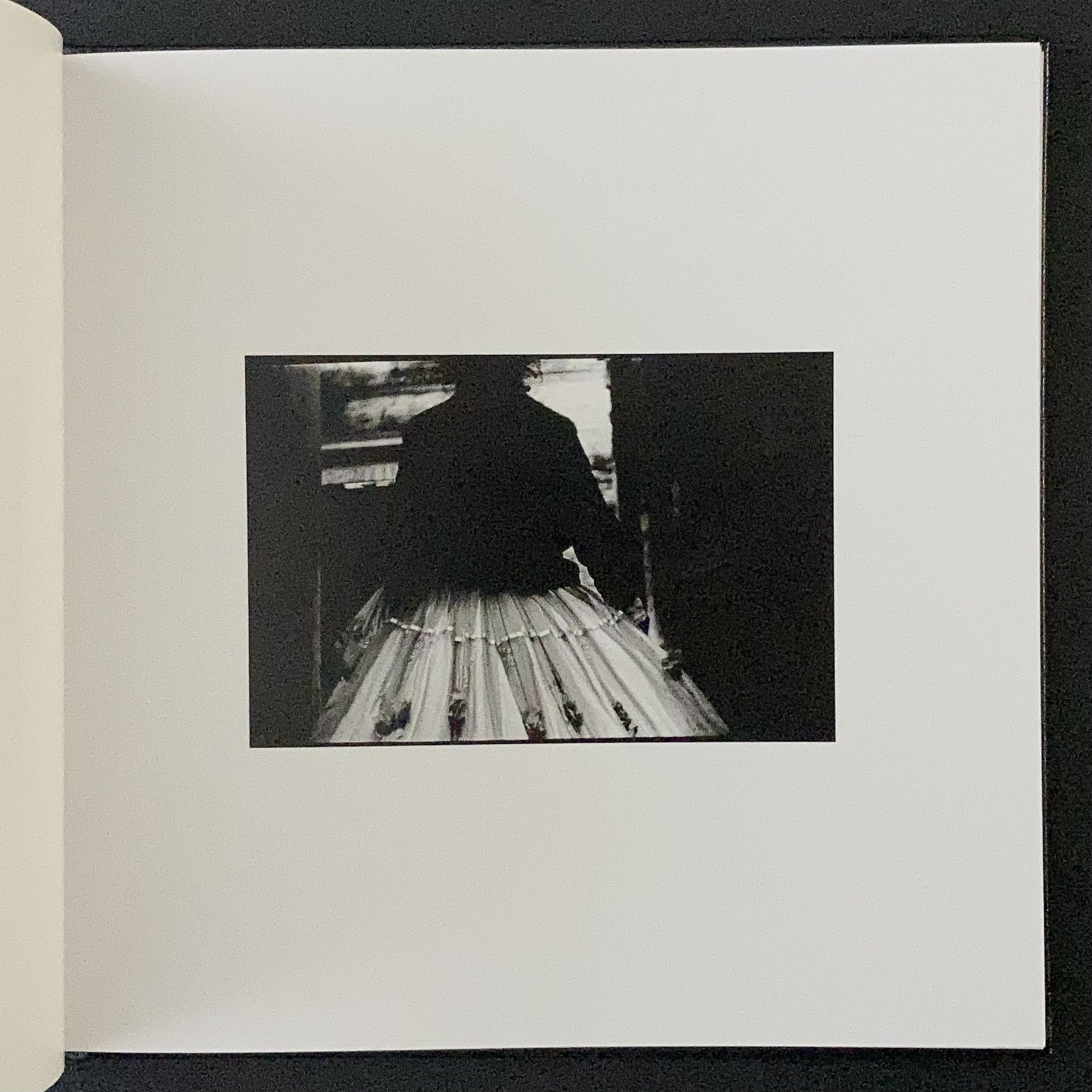

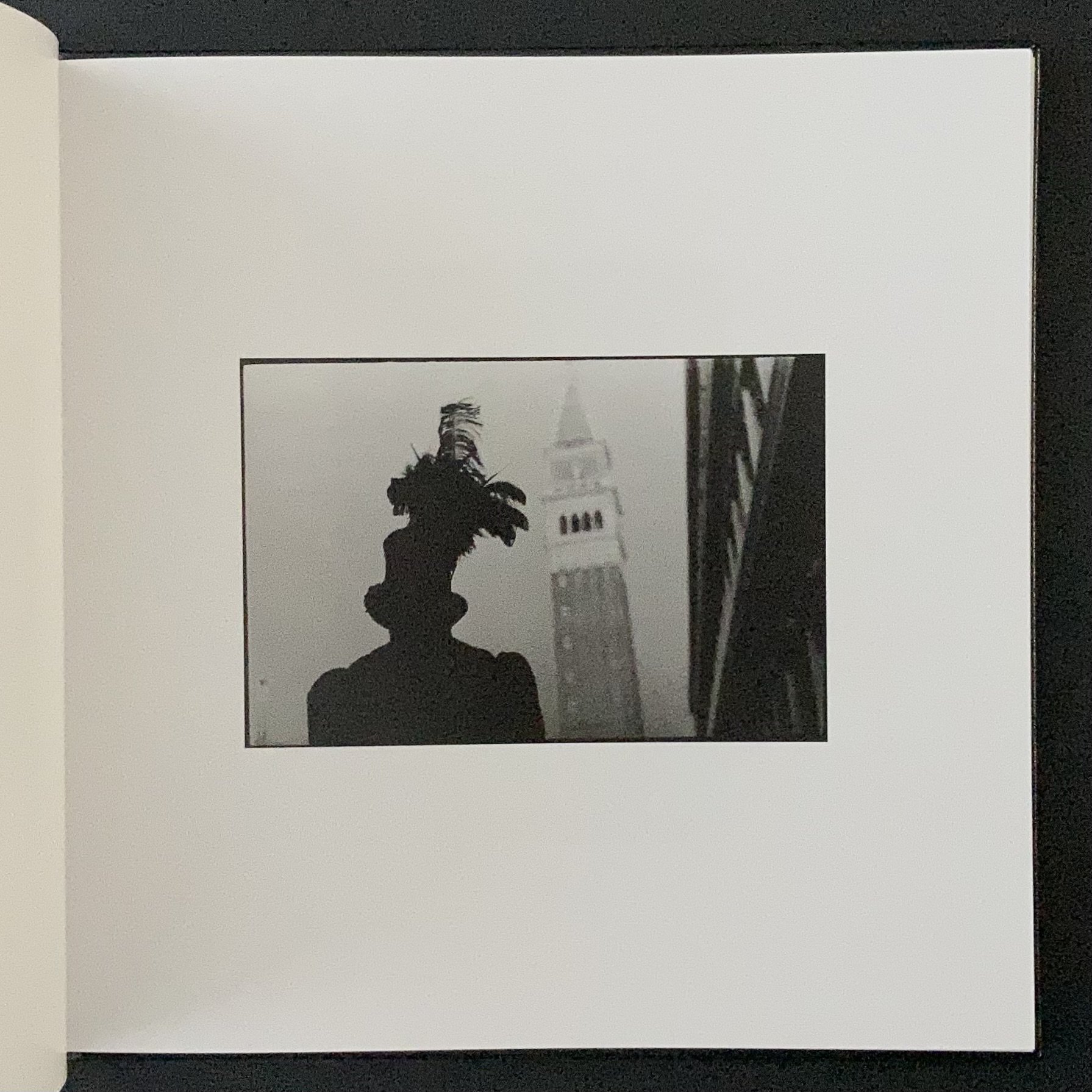

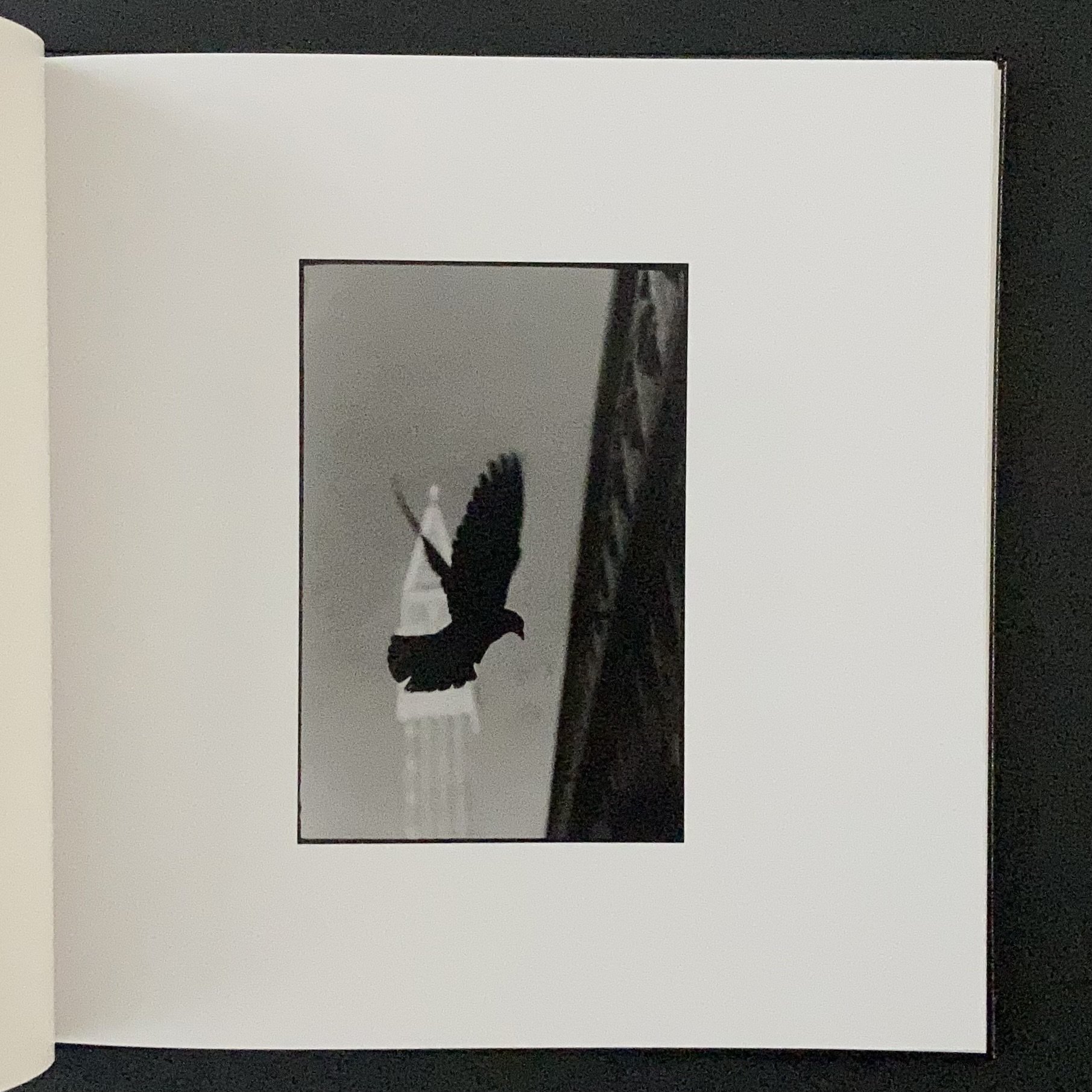

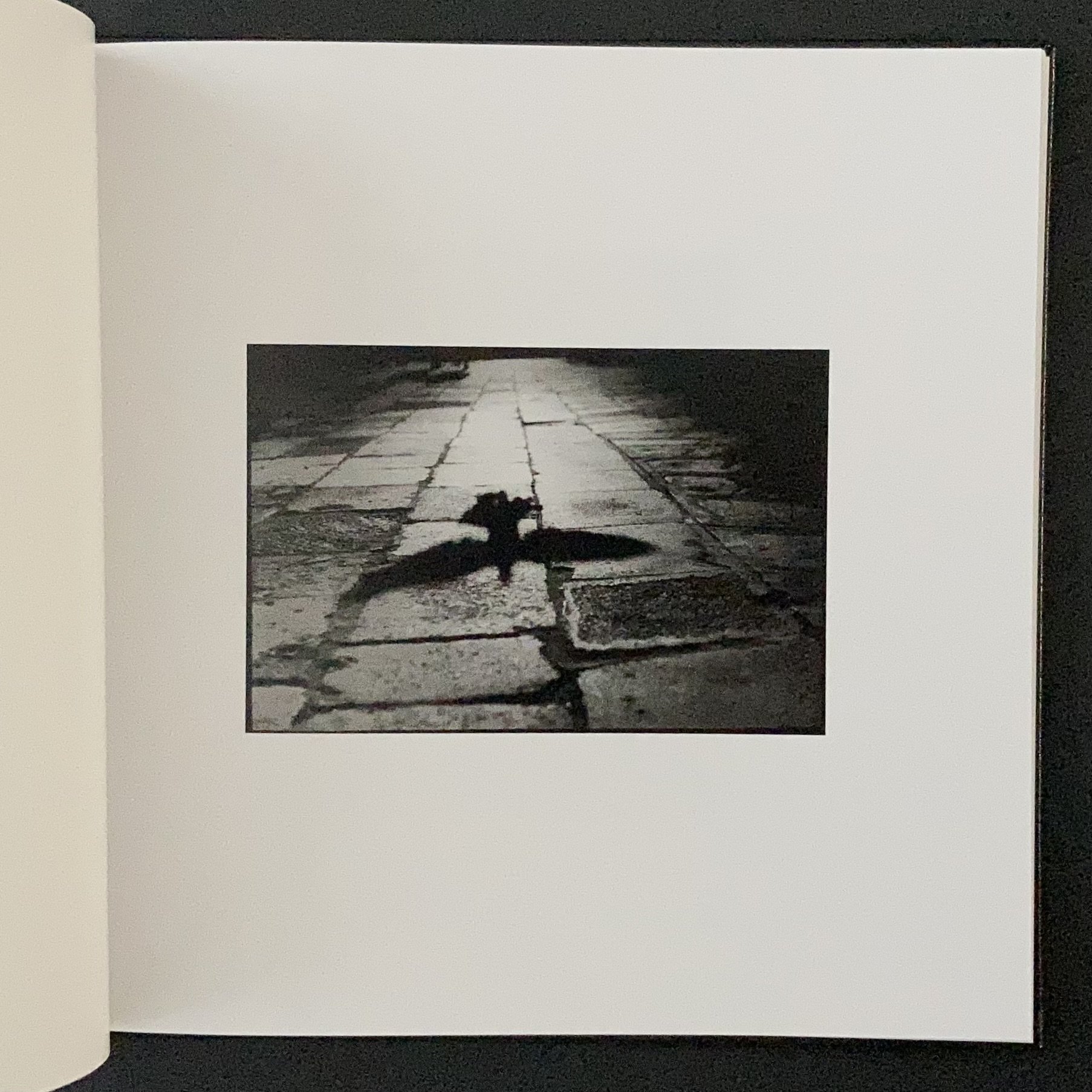

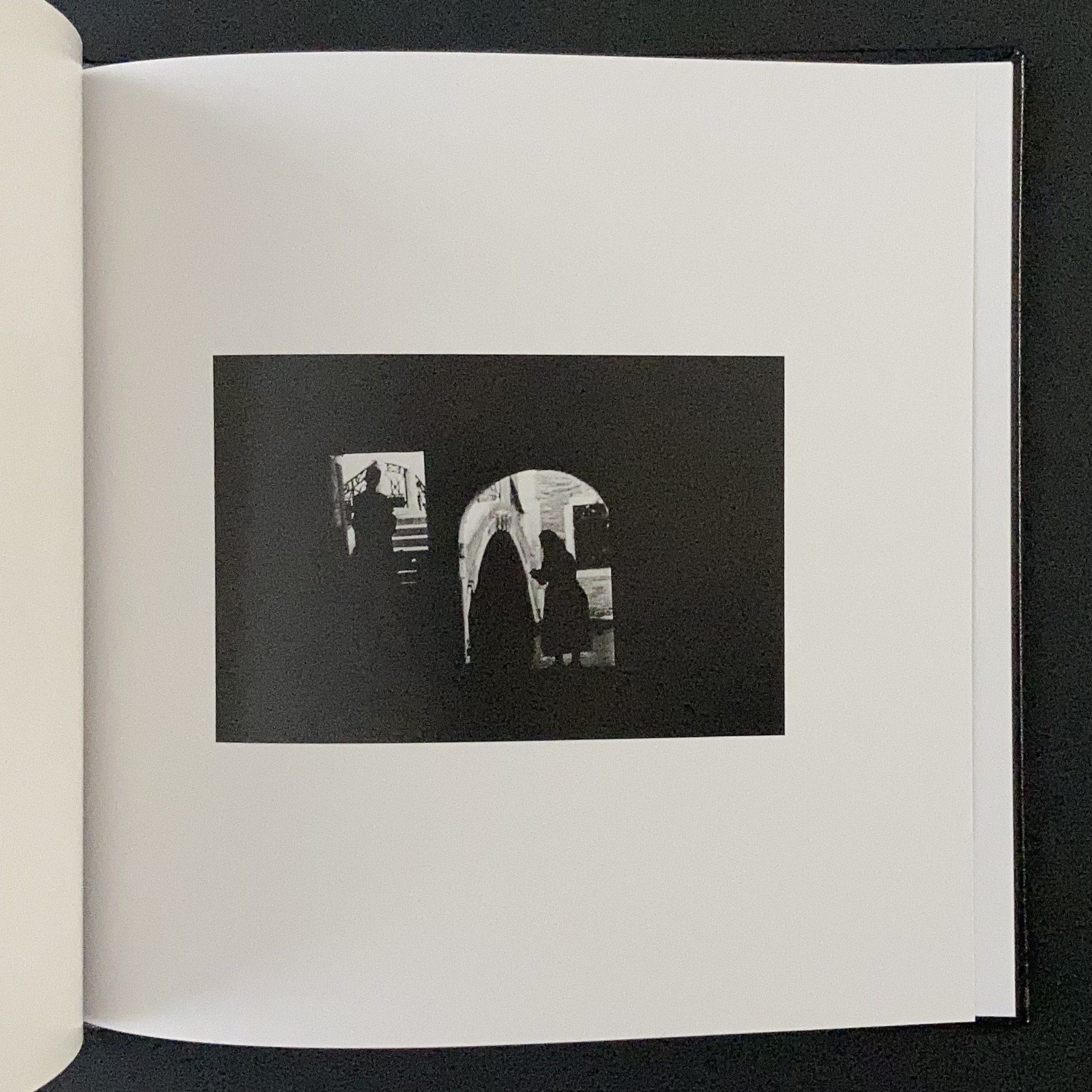

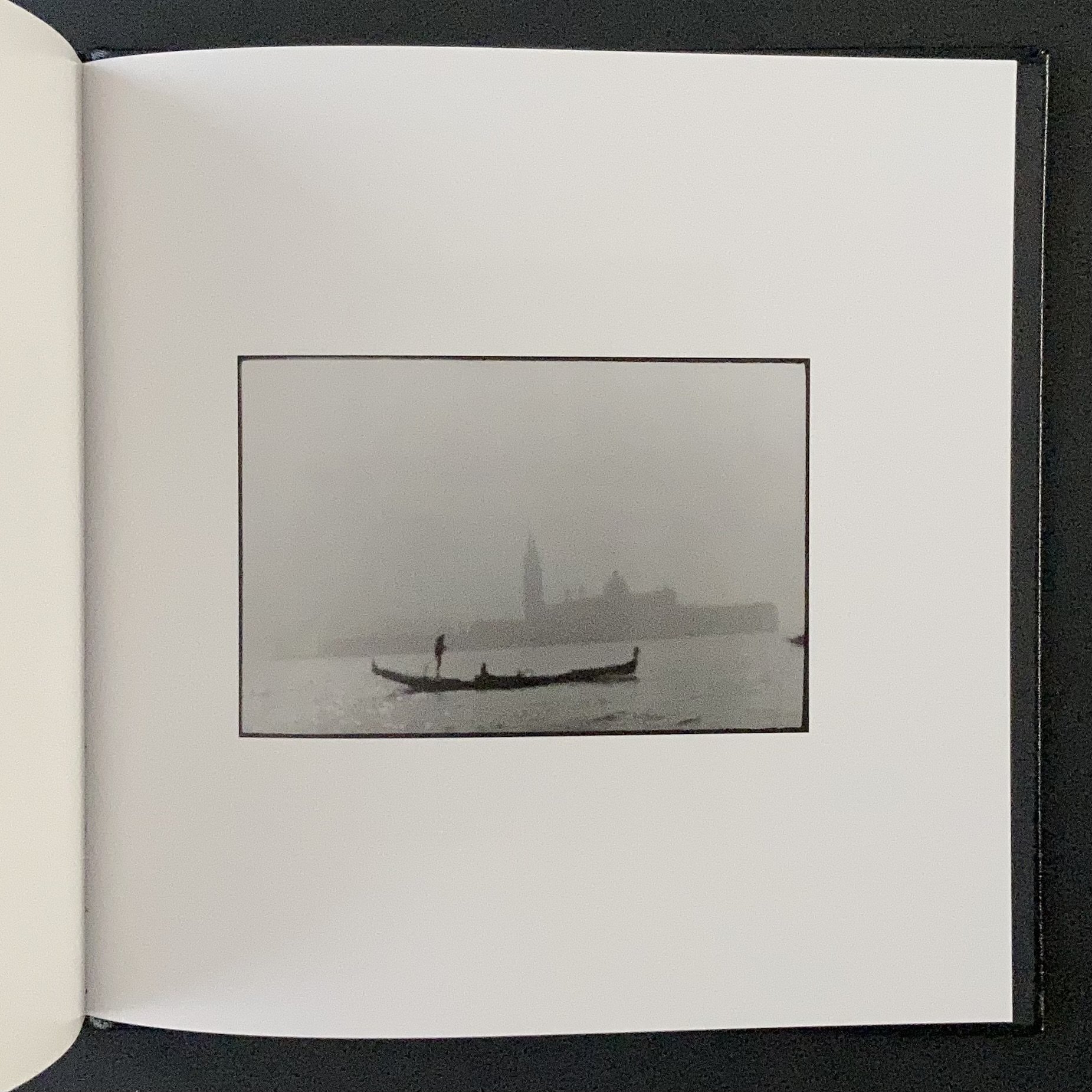

Giacomo Brunelli's latest offering sees him turning his eye and camera to Venice. He says that "Venice is a project I decided to start in response to the fragility of the city after the exceptional November 2019 'Acqua Alta' …" It is his first self-published book and in his unique style, Giacomo gives us an expressionistic and atmospheric interpretation of Venice.

For those not familiar with Giacomo’s work, it can be loosely summed up as film noir street photography. However, he has published books on subjects as diverse as animals (The Animals, his first book) and Self Portraits (published 2017). He has also published New York, Eternal London, and Hamburg.

I first came across Giacomo's work through his book Eternal London (2016), which followed an exhibition at The Photographers' Gallery in 2014. I remember being struck by his style and it left a strong impression on me.

I made a modest contribution to Venice: I was fortunate to work with Giacomo in the very early stages of Venice, mocking up ideas for the cover, and then helping with the digital book layout.

The first 250 copies of Venice are numbered and signed. There are also two limited special editions of with prints (these are not in the book). Venice and other books are available from his website here . Venice is also available at The Photographers' Gallery bookshop here.

I have also made a photobook flip-through of Venice. You can view it on YouTube here.